Introduction

Introduction

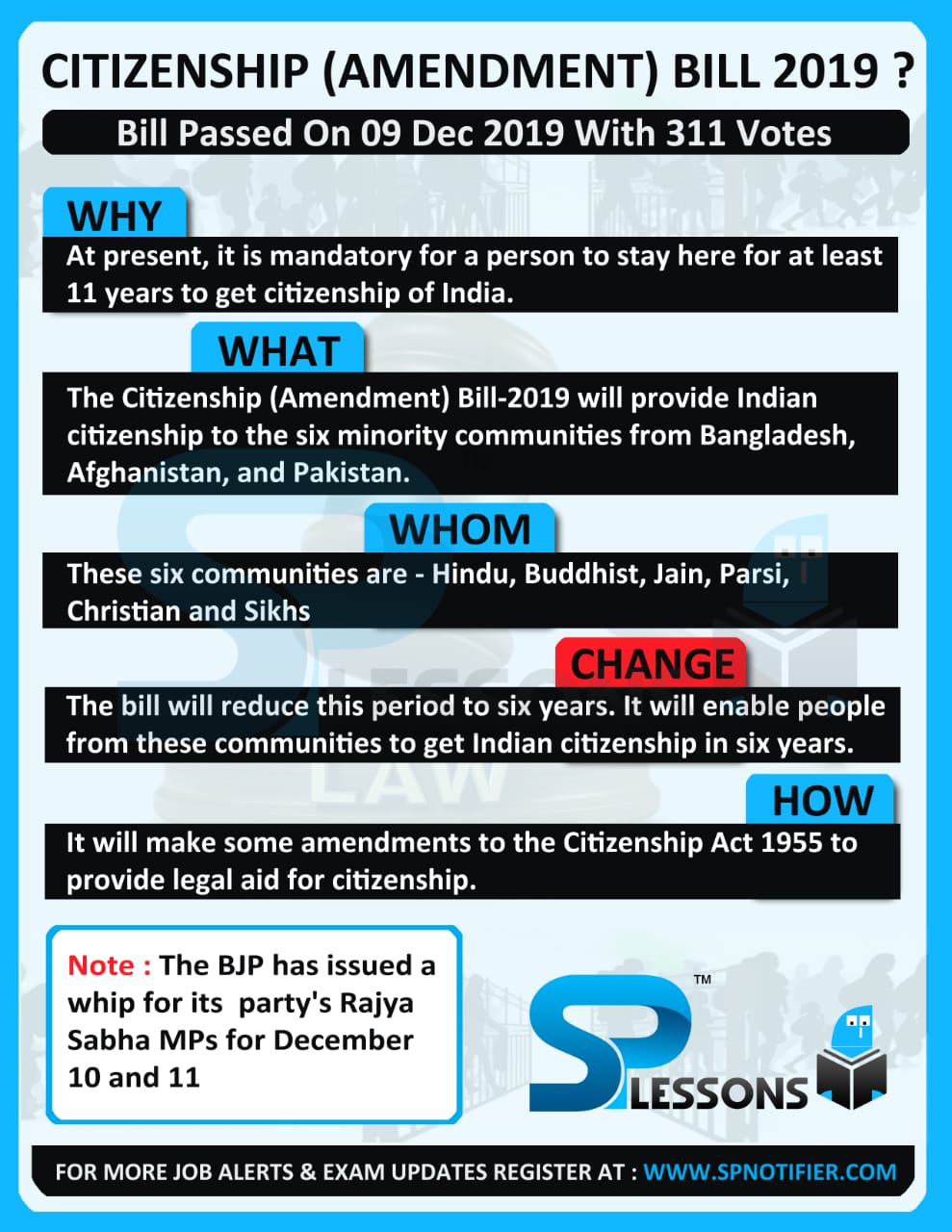

The Citizenship Amendment Bill was first introduced in 2016 by the Lok Sabha by amending the Citizenship Act of 1955. This bill was referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee, whose report was later submitted on January 7, 2019. The Citizenship Amendment Bill was passed on January 8, 2019, by the Lok Sabha which lapsed with the dissolution of the [latex]{16}^{th}[/latex] Lok Sabha. This Bill was introduced again on 9 December 2019 by the Minister of Home Affairs Amit Shah in the [latex]{17}^{th}[/latex] Lok Sabha and was later passed on 10 December 2019. The Rajya Sabha also passed the bill on [latex]{11}^{th}[/latex] December.

CAB

CAB

Citizenship Amendment Bill 2019 - CAB:

The CAB was passed to provide Indian citizenship to the illegal migrants who entered India on or before [latex]{31}^{st}[/latex] December 2014. The bill was passed for migrants of six different religions such as Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Any individual will be considered eligible for this bill if he/she has resided in India during the last 12 months or for 11 of the previous 14 years.

The Bill makes applicants belonging to the said communities from the aforesaid countries eligible for citizenship by naturalization if they can establish their residency in India for 5 years instead of the existing 11 years.

The provisions of the amendments to the Act would not apply to the tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram or Tripura as included in the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution and the area covered under ‘The Inner Line’ notified under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873. Manipur would be brought under the ILP regime.

The Bill seeks to amend section 7D of the act to empower the Central Government to cancel registration as Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) Cardholder in case of violation of any provisions of the Citizenship Act or any other law for the time being in force.

Concern

Concern

The bill makes illegal migrants eligible for citizenship on the basis of religion – a move that may violate Article 14 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees right to equality.

The Bill classifies migrants based on their country of origin to include only Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. it is not clear why migrants from these countries are differentiated from migrants from other neighboring countries such as Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

There has been strong resistance to the Bill in Northeast esp. Assam who fear it would pave the way for granting citizenship mostly to illegal Hindu migrants from Bangladesh, who came after March 1971, in violation of the 1985 Assam Accord.

Citizenship

Citizenship

- Citizenship defines the relationship between the nation and the people who constitute the nation.

- It confers upon an individual certain right such as protection by the state, right to vote and right to hold certain public offices, among others, in return for the fulfillment of certain duties/obligations owed by the individual to the state.

- The Constitution of India provides for a single citizenship for the whole of India.

- Under Article 11 of the Indian Constitution, Parliament has the power to regulate the right of citizenship by law. Accordingly, the parliament had passed the Citizenship act of 1955 to provide for the acquisition and determination of Indian Citizenship.

- Entry 17, List 1 under the Seventh Schedule speaks about Citizenship, naturalization, and aliens. Thus, Parliament has exclusive power to legislate with respect to citizenship.

- Until 1987, to be eligible for Indian citizenship, it was sufficient for a person to be born in India.

- Then, spurred by the populist movements alleging massive illegal migrations from Bangladesh, citizenship laws were first amended to additionally require that at least one parent should be Indian.

- In 2004, the law was further amended to prescribe that not just one parent be Indian; but the other should not be an illegal immigrant.

Articles

Articles

Citizenship in India

Citizenship is the status of a person recognized under law as being a legal member of a sovereign state or belonging to a nation. In India, Articles 5 – 11 of the Constitution deals with the concept of citizenship. The term citizenship entails the enjoyment of full membership of any State in which a citizen has civil and political rights.

First, we discuss all the articles in the Indian Constitution pertaining to citizenship.

Article 5: Citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution

This article talks about citizenship for people at the commencement of the Constitution, i.e., on November 26th, 1949. Under this, citizenship is conferred upon those persons who have their domicile in Indian territory and –

-

1. Who was born in Indian territory; or

2. Whose either parent was born in Indian territory; or

3. Who has ordinarily been a resident of India for not less than 5 years immediately preceding the commencement of the Constitution

Article 6: Citizenship of certain persons who have migrated from Pakistan

Any person who has migrated from Pakistan shall be a citizen of India at the time of the commencement of the Constitution if –

1. He or either of his parents or any of his grandparents was born in India as given in the Government of India Act of 1935; and

2.

- (a) in case such a person has migrated before July [latex]{19}^{th}[/latex], 1948 and has been ordinarily resident in India since his migration, or

(b) in case such as a person has migrated after July [latex]{19}^{th}[/latex], 1948 and he has been registered as a citizen of India by an officer appointed in that behalf by the government of the Dominion of India on an application made by him thereof to such an officer before the commencement of the Constitution, provided that no person shall be so registered unless he has been resident in India for at least 6 months immediately preceding the date of his application.

Article 7: Citizenship of certain migrants to Pakistan

This article deals with the rights of people who had migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947 but subsequently returned to India.

Article 8: Citizenship of certain persons of Indian origin residing outside India

This article deals with the rights of people of Indian origin residing outside India for purposes of employment, marriage and education.

People voluntarily acquiring citizenship of a foreign country will not be citizens of India.

Any person who is considered a citizen of India under any of the provisions of this Part shall continue to be citizens and will also be subject to any law made by the Parliament.

Article 11: Parliament to regulate the right of citizenship by law

The Parliament has the right to make any provision with regard to the acquisition and termination of citizenship and any other matter relating to citizenship.

CoI

CoI

- Citizenship in India is governed by Articles 5 – 11 (Part II) of the Constitution.

- The Citizenship Act, 1955 is the legislation dealing with citizenship. This has been amended by the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 1986, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 1992, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2003, and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2005.

- Nationality in India mostly follows the jus sanguinis (citizenship by right of blood) and not jus soli (citizenship by right of birth within the territory).

Citizenship of India can be acquired in the following ways:

1. Citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution

2. Citizenship by birth

3. Citizenship by descent

4. Citizenship by registration

5. Citizenship by naturalization

6. By incorporation of territory (by the Government of India)

- People who were domiciled in India as on [latex]{26}^{th}[/latex] November 1949 automatically became citizens of India by virtue of citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution.

- Persons who were born in India on or after 26th January 1950 but before [latex]{1}^{st}[/latex] July 1987 are Indian citizens.

- A person born after 1st July 1987 is an Indian citizen if either of the parents was a citizen of India at the time of birth.

- Persons born after [latex]{3}^{rd}[/latex] December 2004 are Indian citizens if both parents are Indian citizens or if one parent is an Indian citizen and the other is not an illegal migrant at the time of birth.

- Citizenship by birth is not applicable for children of foreign diplomatic personnel and those of enemy aliens.

Termination of the citizenship is possible in three ways according to the Act:

1. Renunciation: If any citizen of India who is also a national of another country renounces his Indian citizenship through a declaration in the prescribed manner, he ceases to be an Indian citizen. When a male person ceases to be a citizen of India, every minor child of his also ceases to be a citizen of India. However, such a child may within one year after attaining full age become an Indian citizen by making a declaration of his intention to resume Indian citizenship.

2. Termination: Indian citizenship can be terminated if a citizen knowingly or voluntarily adopts the citizenship of any foreign country.

3. Deprivation: The government of India can deprive a person of his citizenship in some cases. But this is not applicable for all citizens. It is applicable only in the case of citizens who have acquired the citizenship by registration, naturalization or only by Article 5 Clause (c) (which is citizenship at commencement for domicile in India and who has ordinarily been a resident of India for not less than 5 years immediately preceding the commencement of the Constitution).

A person would be eligible for the PIO card if he:

- 1. Is a person of Indian origin and is a citizen of any country except Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China or Afghanistan, or

- 2. Has held an Indian passport at any other time or is the spouse of a citizen of India or a person of Indian origin.

OCI

OCI

- OCI Card is for foreign nationals who were eligible for Indian citizenship on [latex]{26}^{th}[/latex] January 1950 or was an Indian citizen on or after that date.

- Citizens of Pakistan and Bangladesh are not eligible for OCI Card. An OCI cardholder does not have voting rights.

- OCI is not dual citizenship. OCI cardholders are not Indian citizens.

- The OCI Card is a multipurpose, multiple entry lifelong visa for visiting India.

- Persons with OCI Cards have equal rights as NRIs in terms of financial, educational and economic matters. But they cannot acquire agricultural land in India.

Did You Know: The Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) Scheme was introduced by amending the Citizenship Act, 1955 in August 2005 in response to demands for dual citizenship by the Indian diaspora, particularly in developed countries. It was launched during the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas convention at Hyderabad in 2006.

An Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) is a person who is technically a citizen of another country having an Indian origin. They were citizens of India on [latex]{26}^{th}[/latex] January 1950 or thereafter except who is or had been a citizen of Pakistan, Bangladesh or such other countries.

Multi-purpose and life-long visa are provided to the registered Overseas Citizen of India for visiting India and are also exempted from registration with Foreign Regional Registration Officer or Foreign Registration Officer for any length of stay in India.

Launched in 2005, under the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, the OCI card was introduced for fulfilling the demands for dual citizenship among the Indians living in different developed countries. The OCI card provides Overseas Citizenship of India to live and work in India for an indefinite period of time but does not provide the right to vote, hold constitutional offices or buy agricultural properties.

Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) Card: Eligibility

A person must meet the following eligibility criteria before applying for the OCI scheme:

- He/She is a citizen of another country having an Indian origin. He/She was a citizen of India on or before the commencement of the constitution; or

- He/She is a citizen of another country but was eligible for the citizenship of India at the time of the commencement of the constitution; or

- He/She is a citizen of another country and belonging to a territory that became a part of India after the 15th August 1947; or

- He/She is a child/grandchild/great grandchild of such a citizen; or

- He/She is a minor child, whose parents are both Indian citizens or one parent is a citizen of India and is a spouse of foreign origin of an Indian citizen or of an OCI cardholder

Did You Know: Any person having citizenship of Bangladesh or Pakistan is not eligible to apply for the OCI card. Even a person having a background of serving any foreign military are also not eligible for the scheme.

The registered Overseas Citizens of India are not entitled to several rights that are conferred on a citizen of India.

1. Right to equality of opportunity under article 16 of the Constitution with regard to public employment.

2. Right for election as President and Vice-President under article 58 and article 66 respectively.

3. They are not entitled to the rights under article 124 and article 217 of the Constitution.

4. Right to register as a voter under section 16 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950(43 of 1950).

5. Rights with regard to the eligibility for being a member of the State Council/Legislative Assembly/Legislative Council.

6. For an appointment to the posts of Public Services and Union Affairs of any State.

Under the Act, an illegal migrant is a foreigner who:

- Enters the country without valid travel documents like a passport and visa, or

- Enters with valid documents, but stays beyond the permitted time period.

Did You Know: Illegal migrants may be put in jail or deported under the Foreigners Act, 1946 and the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920.

The present scenario that is before the introduction of the bill

- Under the existing laws, an illegal migrant is not eligible to apply for acquiring citizenship. They are barred from becoming an Indian citizen through registration or naturalization.

- The Foreigners Act and the Passport Act debar such a person and provide for putting an illegal migrant into jail or deportation.

- A person can become an Indian citizen through registration.

- Section 5 (a) of Citizenship act of 1955: A person of Indian origin who is ordinarily resident in India for seven years before making an application for registration;

- And they should have lived in India continuously for 12 months before submitting an application for citizenship.

- Under the Citizenship Act, 1955, one of the requirements for citizenship by naturalization is that the applicant must have resided in India during the last 12 months, as well as for 11 of the previous 14 years.

- The Citizenship Amendment Bill 2019 aims to make changes in the Citizenship Act, the Passport Act, and the Foreigners Act if the illegal migrants belong to religious minority communities from three neighboring countries of Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

- Simply put, the Citizenship Amendment Bill will grant the illegal non- Muslim migrants the status of legal migrants despite them having come to India without valid documents and permission.

- The Bill seeks to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955 to make Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian illegal migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, eligible for citizenship of India. In other words, the Bill intends to make it easier for non-Muslim immigrants from India’s three Muslim-majority neighbors to become citizens of India.

- The legislation applies to those who were “forced or compelled to seek shelter in India due to persecution on the ground of religion”. It aims to protect such people from proceedings of illegal migration.

- The amendment relaxes the requirement of naturalization from 11 years to 5 years as a specific condition for applicants belonging to these six religions.

- The cut-off date for citizenship is December 31, 2014, which means the applicant should have entered India on or before that date.

- The Bill says that on acquiring citizenship:

- Such persons shall be deemed to be citizens of India from the date of their entry into India, and

- All legal proceedings against them in respect of their illegal migration or citizenship will be closed.

- It also says people holding Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) cards – an immigration status permitting a foreign citizen of Indian origin to live and work in India indefinitely – can lose their status if they violate local laws for major and minor offenses and violations.

-

The Bill adds that the provisions on citizenship for illegal migrants will not apply to the tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura, as included in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution.

- These tribal areas include Karbi Anglong (in Assam), Garo Hills (in Meghalaya), Chakma District (in Mizoram), and Tripura Tribal Areas District.

- It will also not apply to the areas under the Inner Line Permit under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873.

- The Inner Line Permit regulates the visit of Indians to Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Nagaland.

Criticism

Criticism

- The fundamental criticism of the Bill has been that it specifically targets Muslims. Thus, the religious basis of citizenship not only violates the principles of secularism but also of liberalism, equality, and justice.

- It fails to allow Shia, Balochi and Ahmadiyya Muslims in Pakistan and Hazaras in Afghanistan who also face persecution, to apply for citizenship.

- A key argument against the CAB is that it will not extend to those persecuted in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, from where Rohingya Muslims and Tamils are staying in the country as refugees.

- Neither is religious persecution the monopoly of three countries nor is such persecution confined to non-Muslims.

- Critics argue that it is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to equality.

- The CAB is in the teeth of Article 14, which not only demands reasonable classification and a rational and just object to be achieved for any classification to be valid but additionally requires every such classification to be non-arbitrary.

- The Bill is an instance of class legislation, as classification on the ground of religion is not permissible.

- In the Northeastern states, the prospect of citizenship for massive numbers of illegal Bangladeshi migrants has triggered deep anxieties, including fears of demographic change, loss of livelihood opportunities, and erosion of the indigenous culture.

- The Bill appears to violate the Assam Accord, both in letter and spirit.

- The Assam Accord, signed between the then Rajiv Gandhi-led central government and the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), had fixed March 24, 1971, as the cutoff date for foreign immigrants. Those illegally entering Assam after this date were to be detected and deported, irrespective of their religion.

- The Citizenship Amendment Bill moved the cutoff date for six religions to December 31, 2014, something that is not acceptable to the Assamese- speaking people in Brahmaputra Valley, who insist that all illegal immigrants should be treated as illegal.

- There is also an economic problem. If tens of thousands leave Bangladesh and start staying legally in Assam and North East, the pressure will first show in the principal economic resource—land.

- Also, since these will be legitimate citizens, there will also be more people joining the queue of job hopefuls that can potentially lower opportunities for the indigenous and the locals.

- It also boils down to the political rights of the people of the state. Migration has been a burning issue in Assam.

- There is a view that illegal immigrants, who will eventually become legitimate citizens, will be determining the political future of the state.

- CAB does not consider Jews and atheists. They have been left out of the bill.

- The basis of clubbing Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh together and thereby excluding other (neighboring) countries is unclear.

- A common history is not ground as Afghanistan was never a part of British India and was always a separate country. Being a neighbor, geographically, is no ground too as Afghanistan does not share an actual land border with India.

- Countries such as Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar, which share a land border with India, have been excluded.

- The reason stated in the ‘Statement of Objects and Reasons’ of the Bill is that these three countries constitutionally provide for a “state religion”; thus, the Bill is to protect “religious minorities” in these theocratic states.

- The above reasoning fails with respect to Bhutan, which is a neighbor and constitutionally a religious state with the official religion being Vajrayana Buddhism.

- Non-Buddhist missionary activity is limited, construction of non- Buddhist religious buildings is prohibited and the celebration of some non-Buddhist religious festivals is curtailed. Yet, Bhutan has been excluded from the list.

- On the classification of individuals, the Bill provides benefits to sufferers of only one kind of persecution, i.e. religious persecution neglecting others.

- Religious persecution is a grave problem but political persecution is also equally existent in parts of the world. If the intent is to protect victims of persecution, the logic to restrict it only to religious persecution is suspect.

- The seemingly unconstitutional provisions of the CAB will deny equal protection of laws to similarly placed persons who come to India as “illegal migrants” but in fact grant citizenship to the less deserving at the cost of the more deserving.

- The provisions of CAB might lead to a situation where a Rohingya who has saved himself from harm in Myanmar by crossing into India will not be entitled to be considered for citizenship, while a Hindu from Bangladesh, who might be an economic migrant and have not faced any direct persecution in his life, would be entitled to citizenship.

- Similarly, a Tamil from Jaffna escaping the atrocities in Sri Lanka will continue to be an “illegal migrant” and never be entitled to apply for citizenship by naturalization.

- There is also a reduction in the residential requirement for naturalization — from 11 years to five. The reasons for the chosen time frame has not been stated.

Arguments

Arguments

It is not against Muslims:

- The Ahmediyas and Rohingyas can still seek Indian citizenship through naturalization (if they enter with valid travel documents).

- In any case, since India follows the principle of non-refoulment (even without acceding to the Refugee Convention 1951), they would not be pushed back.

- If a Shia Muslim is facing persecution and is in India seeking shelter, his case to continue to reside in India as a refugee shall be considered on its merits and circumstances.

- With regard to Balochi refugees, Balochistan has long struggled to be independent of Pakistan and including Balochis in the CAB could be perceived as interference in Pakistan’s internal affairs.

- The CAB, therefore, does not exclude Muslims from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan to apply for Indian citizenship. They can continue to do so in the same way singer Adnan Sami, for example, applied for citizenship.

- It is important to note that even minorities shall not be granted automatic citizenship. They would need to fulfill conditions specified in the Third Schedule to the Citizenship Act, 1955, namely, the good character requirement as well as physical residence in India

- Harish Salve, one of India’s biggest names in national and international law, has stated that the Citizenship Amendment Bill is not anti-Muslim

- Salve stated that the countries specified in the CAB have their own state religion and Islamic rules. He added that Islamic majority nations identify their people as per who follows Islam and who does not. Addressing governance problems in neighboring countries is not the purpose of the CAB.

- Over the issue of Rohingyas, Salve stated that a law that addresses one evil does not need to address all the evils in all countries. It is notable here that Myanmar, though a Buddhist majority nation, does not have a state religion and Myanmar does not feature in CAB .

Sovereign space

To begin with, the justiciability of citizenship or laws that regulate the entry of foreigners is often treated as a ‘sovereign space’ where the courts are reluctant to intervene.

Thus in Trump v Hawaii No. 17-965, 585 U.S. (2018), the US Supreme Court upheld travel ban from several Muslim countries holding that regulation of foreigners including ingress is “fundamental sovereign attribute exercised by the government’s political departments largely immune from judicial control.”

Indian courts have generally followed similar reasoning. In David John Hopkins vs. Union of India (1997), the Madras High Court held that the right of the Union to refuse citizenship is absolute and not fettered by equal protection under Article 14.

Similarly in Louis De Raedt vs. Union of India (1991), the Supreme Court held that the right of a foreigner in India is confined to Article 21 and he cannot seek citizenship as a matter of right.

- Citizenship Amendment Bill does not dilute the sanctity of the Assam Accord as far as the cut-off date of March 24, 1971, stipulated for the detection/deportation of illegal immigrants is concerned.

- Citizenship Amendment Bill is not Assam-centric. It is applicable to the whole country. Citizenship Amendment Bill is definitely not against the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which is being updated to protect indigenous communities from illegal immigrants.

- Further, there is a cut-off date of December 31, 2014, , and benefits under the Citizenship Amendment Bill will not be available for members of the religious minorities who migrate to India after the cut-off date.

Historical

Historical

- The proposed bill does not give a carte blanche to Hindus and Christians and Sikhs from other countries to come to India and get citizenship. Just these three countries. Why?

- Because each of these has been civilizational tied with India. The circumstances in which they were partitioned from India have created a situation where Hindus and other minority populations have been dwindling ever since the partition took place.

- Regarding including other countries in the neighborhood the argument could be that we can deal with them separately if the need arises as we did in the case of persecuted Sri Lankan Tamils.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The parliament has unfractured powers to make laws for the country when it comes to Citizenship. But the opposition and other political parties allege this bill by the Government violates some of the basic features of the constitution like secularism and equality. It may reach the doors of the Supreme Court where the Supreme Court will be the final interpreter. If it violates the constitutional features and goes ultra- wires it will be struck down, if it is not we will have a new law.

But one thing that is most important is, an equilibrium has to be attained by New Delhi as this involves neighboring countries too. Any exaggerated attempt to host the migrants should not be at the cost of goodwill earned over the years. India being a land of myriad customs and traditions, the birthplace of religions and the acceptor of faiths and protectors of persecuted in the past should always uphold the principles of Secularism going forward.

NLP

NLP

- It was an agreement between the Governments of India and Pakistan regarding Security and Rights of Minorities that was signed in Delhi in 1950 between the Prime ministers of India and Pakistan, Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan

- The need for such a pact was felt by minorities in both countries following Partition, which was accompanied by massive communal rioting.

- In 1950, as per some estimates, over a million Hindus and Muslims migrated from and to East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh), amid communal tension and riots such as the 1950 East Pakistan riots and the Noakhali riots.

- refugees were allowed to return unmolested to dispose of their property

- abducted women and looted property were to be returned

- forced conversions were unrecognized

- minority rights were confirmed

- The Governments of India and Pakistan solemnly agree that each shall ensure, to the minorities throughout its territory, complete equality of citizenship, irrespective of religion, a full sense of security in respect of life, culture, property and personal honor, freedom of movement within each country and freedom of occupation, speech and worship, subject to law and morality,” the pact said.

- “Members of the minorities shall have equal opportunity with members of the majority community to participate in the public life of their country, to hold political or another office, and to serve in their country’s civil and armed forces. Both Governments declare these rights to be fundamental and undertake to enforce them effectively.”